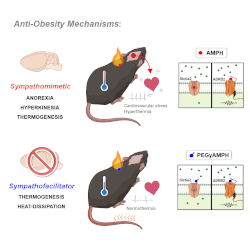

Currently, the most effective anti-obesity drugs are amphetamine-like drugs, which are thought to promote weight loss by acting on the brain to cause loss of appetite and increased locomotor activity. However, in addition to being addictive, these drugs can have dangerous side effects such as increased heart rate, hypertension and hyperthermia.

Now, Dr Gonçalo Bernardes and Associate Professor Ana Domingos of the University of Oxford, with colleagues in Portugal, have created a new type of amphetamine, and have shown in mice that it does not have behavioural effects or the dangerous side effects of unmodified amphetamines.

Amphetamines tend to accumulate in the brain, but they have been traditionally classified as sympathomimetic drugs because they affect the sympathetic neurons, which constitute the part of the peripheral nervous system known to accelerate the heart rate, constrict blood vessels and raise body temperature.

It was previously thought that the effects on the cardiovascular system were not caused by the amphetamines’ action in the brain, but rather by their direct stimulation of the cardiac sympathetic nerves.

However, Bernardes and Domingos suspected that the cardiac side effects of amphetamines could originate in the brain. If this were true, they hypothesized that if they could design a drug that did not pass the blood-brain barrier, they could avoid these unwanted outcomes but still retain the desired anti-obesity action.

“This discovery could drive research into a whole new way of treating obesity.” Gonçalo Bernardes

The two had published a previous study in which they had modified a protein to allow targeted elimination of the sympathetic neurons that stimulate nerves in adipose tissue and control the breakdown of fat stores in the body. With this approach, mice became obese despite having the same feeding behaviour as the control animals. In fact, it has been reported that while some humans readily store excess fat with overeating, others appear to resist fat gain. “This knowledge inspired the hypothesis that if we could do the reverse approach and stimulate those same sympathetic neurons, maybe we could cause the mice to lose weight,” said Bernardes.

To prove their hypothesis, Bernardes and Domingos, working with researchers in Portugal, attached polyethylene glycol (PEG) polymer chains to amphetamine, in a process known as PEGylation. PEGylation is often used to mask a drug from the body’s immune system, or to increase the hydrodynamic size (size in solution) of molecules. Through this process, they created a larger, PEGylated amphetamine, which they dubbed PEGyAMPH. “This is the first time that a pegylated amphetamine has been used in this way,” noted Bernardes, “and its physiologic effect needed further testing in order to explore the anti-obesity potential of this new drug.”

Because of its larger size, PEGyAMPH cannot penetrate the blood-brain barrier and affect behaviour. Instead, the researchers were able to show that it binds to the β2-adrenoceptor (ADRB2), which stimulates peripheral sympathetic neurons in adipose tissues. This causes the mice to lose weight by breaking down the fat stores in the body, combined with activating thermogenesis, which is the process of converting calories into heat.

Because of its larger size, PEGyAMPH cannot penetrate the blood-brain barrier and affect behaviour. Instead, the researchers were able to show that it binds to the β2-adrenoceptor (ADRB2), which stimulates peripheral sympathetic neurons in adipose tissues. This causes the mice to lose weight by breaking down the fat stores in the body, combined with activating thermogenesis, which is the process of converting calories into heat.

“Surprisingly, PEGyAMPH is not only cardio-neutral, meaning it does not elevate the heart rate,” explained Inês Mahú, the first author in this study. “But we also found that it induces peripheral vasodilation (widening of the blood vessels). This increases heat-dissipation, which further boosts energy expenditure without causing hyperthermia.”

“This is different from the way conventional amphetamines work, and it suggests that their physiologic effects are more important for weight-loss than the behavioural ones, which is why it is so exciting,” said Bernardes. “The discovery that peripheral ADRB2 was a main target of the pegylated amphetamine could drive research into a whole new way of treating obesity.”

The team also used different drug delivery approaches to confirm that the cardiovascular effects of amphetamines are not caused peripherally, but are rather driven centrally from the brain. Because PEGyAMPH does not cross the blood-brain barrier, it does not cause these cardiovascular side effects, unless directly delivered to the brain.

This study clearly demonstrates that the newly designed drug has several advantages over traditional amphetamine-based treatments for weight loss. In addition to the weight loss benefits, another significant advantage of PEGyAMPH treatment is that it prevents the increase of blood glucose typically associated with obesity. “This is incredibly important,” said Bernardes. “The new molecule can improve blood glucose levels by increasing sensitivity to insulin.” This prevents hyperinsulinemia, a condition that precedes the development of type 2 diabetes. “We are thrilled that this drug could play an important role in the prevention of type 2 diabetes, which is one of the fastest growing health challenges of this century,” he said.

Obesity is a major health issue across the world, and is implicated not only in type 2 diabetes, but other serious health conditions such as heart disease and cancer. Although still in the experimental stages, this new weight-loss drug brings hope for a safer and more effective treatment than currently available.