The eruption of the Toba volcano was the largest volcanic eruption in the past two million years, but its impacts on climate and human evolution have been unclear. Resolving this debate is key to an understanding of how the eruption affected the environment during during a key interval in human evolution.

Now a Rutgers-led study which appears in the journal PNAS has shed light on this issue. Co-author Dr Anja Schmidt from this Department said: “Our work is not only a forensic analysis of Toba’s aftermath some 74,000 years ago, but also helps us understand the unevenness of the effects very large eruptions may have on today’s society. Ultimately, this will help to mitigate the environmental and societal hazards from future volcanic eruptions.”

“We know this eruption happened and that past climate modeling has suggested the climate consequences could have been severe, but archaeological and paleoclimate records from Africa don't show such a dramatic response,” said lead author Benjamin Black, an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Rutgers University. “We used a large number of climate model simulations to resolve what seemed like a paradox.”

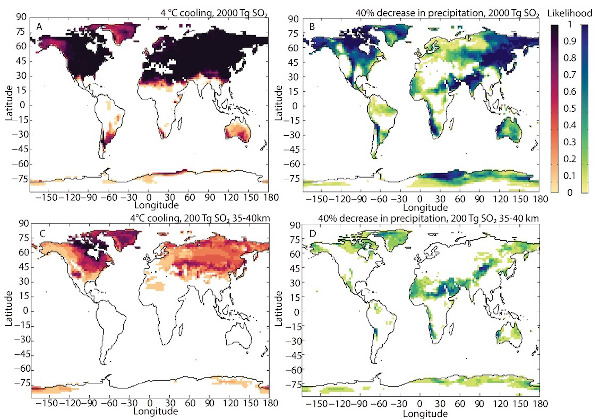

The researchers analysed 42 global climate model simulations in which they varied the magnitude of sulfur emissions, time of year of the eruption, background climate state and sulfur injection altitude. Using these results, they made a probabilistic assessment of the range of climate disruptions the Toba eruption may have caused.

The researchers found there was likely significant regional variation in climate impacts. The simulations predict cooling in the Northern Hemisphere of at least 4°C, with regional cooling as high as 10°C depending on the model parameters. In contrast, even under the most severe eruption conditions, cooling in the Southern Hemisphere -- including regions populated by early humans -- was unlikely to exceed 4°C, although regions in southern Africa and India may have seen decreases in precipitation at the highest sulfur emission level.

Likelihood of a surface cooling of at least 4 degrees Celsius and a 40% decrease in precipitation after the Toba eruption as predicted by the climate model simulations for two scenarios representing the upper and lower amounts of sulfur emitted into the atmosphere during the eruption.

Effect on early human populations

“Our results suggest that we might not have been looking in the right place to see the climate response,” said Black. “Africa and India are relatively sheltered, whereas North America, Europe and Asia bear the brunt of the cooling. One intriguing aspect of this is that Neanderthals and Denisovans were living in Europe and Asia at this time, so our paper suggests evaluating the effects of the Toba eruption on those populations could merit future investigation."

The results explain independent archaeological evidence suggesting the Toba eruption had modest effects on the development of hominid species in Africa. According to the authors, their ensemble simulation approach could be used to better understand other past and future explosive eruptions.

The study was supported by funding from the National Environmental Research Council in the UK and the National Science Foundation in the US, and included researchers from Rutgers University, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, the University of Leeds and the University of Cambridge.

Research

Global climate disruption and regional climate shelters after the Toba supereruption, B.A. Black, J. Lamarque, D.R. Marsh, A. Schmidt, C. Bardeen, PNAS (2021).