When Surabhi Agrawal decided to apply for a postgraduate degree in the UK, she had plenty of advice on how to go about it. Both of Surabhi’s older sisters (like Surabhi) had completed their undergraduate degrees in India. They had then entered postgraduate programmes in the UK, and were able to guide her through the intricacies of selecting the right course, writing a statement, and completing the application forms.

Inspired by the support she received from her sisters, last year Surabhi founded The Bhagini Project. The purpose of the project is to encourage Indian women to pursue higher education by providing mentors who can advise them on how to select and apply for postgraduate courses outside of India. Surabhi chose the name “Bhagini” because it means “elder sister” in ancient Sanskrit.

The Bhagini Project logo

Matching students with mentors

“When I was applying for my Master's and PhD degrees, I was able to rely on the help of my sisters,” recalls Surabhi. “But if you don’t know who to ask, it takes a lot of courage to randomly email somebody and ask if they can help. If there’s a platform that you can use, it makes it much easier.”

In the brief time since it was founded, Surabhi proudly notes that The Bhagini Project has matched over 30 Indian undergraduate students with mentors in fields ranging from the sciences to history, philosophy and law. The project is aimed specifically at helping women. “Girls face a higher barrier to education because of cultural norms and societal pressures. Through the project, we want to highlight women who have broken these barriers and encourage others to pursue their dreams,” explains Surabhi.

Almost all of the mentors have completed an undergraduate degree in India and a postgraduate degree in a different country. “This is important,” explains Surabhi, “because they understand the Indian system, but are also familiar with what is needed to study in other countries.” Surabhi and her sisters are all mentors, of course, and Surabhi spent a lot of time asking friends, acquaintances, colleagues and even people she didn’t know on LinkedIn to become mentors. “I got so many positive responses back,” she smiles.

Mentors can help in all sorts of ways. “This year in one or two cases, people hadn’t even heard of a particular course which the mentor told them about. That was the idea of the project – you have an accessible role model who can guide you a little bit. Also, most of the mentors are just postgraduates ourselves - I think because we’re only a couple of years ahead, we are easier to approach, and we have also had recent experience with the system.”

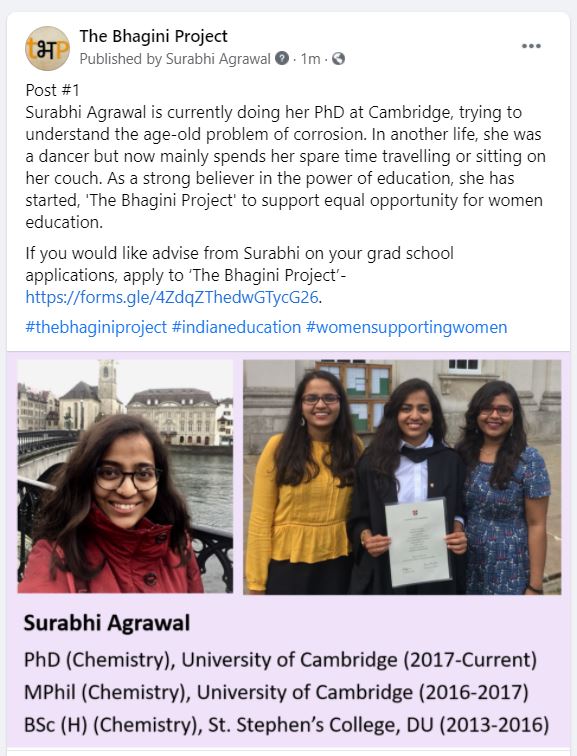

Surabhi's Bhagini Project profile

Surabhi's Bhagini Project profile

A labour of love

For Surabhi, the project really is a labour of love. “Initially it took a lot of time when we were first trying to get mentors, and now I just work every Saturday,” she says modestly. So far, the results have been rewarding: Surabhi knows of at least five mentees who have been accepted into postgraduate programmes, including two who will start in the Department of Chemistry in October.

The Bhagini Project has Facebook and Instagram accounts, where application forms and mentor profiles can be accessed. Applicants are then matched up with a mentor in their field. “Because this was our first year and we were still building a mentor base, if no mentors matched someone’s application, we would go out and find somebody!” confesses Surabhi. Once the Facebook and Instagram accounts were online, Surabhi says she was sometimes even contacted by women who offered to be mentors. “They said: ‘I found it difficult, I’ll help others.’”

Research

Surabhi herself is now in her fourth year of her PhD in Professor Stuart Clarke’s group, where she has been studying the “age-old problem” of corrosion. Covid prevented her from completing much of her experimental work last year, but she now has access to the equipment she needs, although she says she still may need to apply for an extension to complete her lab work before writing up.

As a strong believer in the power of education, especially for women, Surabhi’s advice to anyone thinking of applying for a postgraduate degree is: “I would first say – just apply. I hear so much hesitation in people who think they’re not good enough, but they are. Time is also a big factor. If you’re applying, you should think about it in July, so there’s time to contact the supervisors, see what you’re interested in and find out who is interested in you as a student.”

Corrosion video

Last year Surabhi applied to participate in a Cambridge Creative Encounters project, which matched researchers with a creative film-maker in order to create a short film about their research. Surabhi’s original idea was to convey her research in the form of Kathak, an Indian classical dance form in which she is trained. “I wanted to tell the story of my PhD through dance,” says Surabhi. “I applied to do a dance video but they matched me up with an animator instead. I thought, okay, maybe I’m not dancing but this still seems fun!”

Surabhi loved her collaboration with creative Ali Assaf, and the result was a two-minute animated film about Surabhi’s research into corrosion, which was shown during the Cambridge Festival. You can watch the film here: