One of Fahmida's drawings - Fahmida loves the combination of art and science

Fourth-year PhD student Fahmida Khan loves the Renaissance, that period of European history when philosophy, literature, and the natural sciences blossomed, and art was transformed through the application of new scientific knowledge.

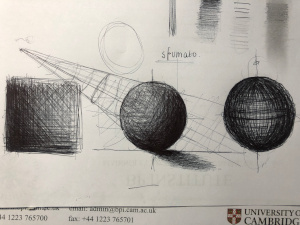

“I love the way artists started using scientific principles, including the newly discovered ways to depict light, to develop their art,” she explains enthusiastically. Fahmida is particularly interested in Leonardo da Vinci, whose experiments in optics and human vision led him to favour ‘sfumato,’ in which fine shading creates a soft transition between colours and tones to achieve a more believable image. “I liked how Leonardo and others mixed art and science,” she says.

One of the drawings Fahmida used when presenting a drawing tutorial for her research group, in which she explains sfumato.

Fahmida herself has always been fascinated by both art and science from an early age. ”This goes a long way back,” she smiles. “When I was a child I was introduced to one of the laboratories in Cambridge, and ever since then I was interested in labs and the ways scientists work, so I made up my mind I wanted to do a PhD.” But Fahmida also loved art, and at high school in Luton she combined chemistry, physics, maths and art, continuing these subjects through A levels.

“That was when I started looking into the Renaissance and realising that a lot of the artists were polymaths – Leonardo was one of my models, because he was interested in so many different things. A lot of his art books look like diagrams you see in a thesis,” she explains. “I liked how people in the Renaissance era had that common theme.”

The golden ratio

While still at school Fahmida also did a project on the golden ratio and how it applies to both art and science. For example, Penrose tiles, discovered by Roger Penrose in the 1970s, use shapes based on the golden ratio (designated as Phi or 1.618) to cover a two-dimensional area in five-fold symmetry, and Dan Shechtman’s Nobel Prize winning discovery of quasi-crystals have a three-dimensional five-fold symmetry defined by the golden ratio. “But Leonardo also used the golden ratio in his drawings and paintings, and that kept me interested in art,” she says.

Fahmida went to University College London for her undergraduate degree, where she combined physics with surface chemistry, while also working in a research group at Imperial College. Following her life-long dream, she then applied for a PhD at Cambridge. Her degree in Chemical Physics turned out to be a good fit with Stuart Clarke’s materials research group.

Research

In the Clarke group Fahmida has been researching passivation, and in particular finding effective ways to prevent steel structures from corroding. Like many other researchers, Fahmida’s experiments were interrupted by Covid, but she believes she will have sufficient results to finish up by her autumn deadline, and she is trying to stay hopeful.

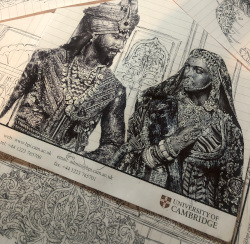

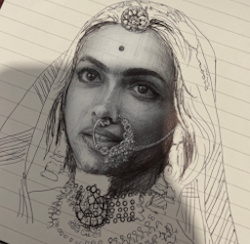

Fahmida started drawing images from the film Padmaavat (below).

Although Fahmida didn’t have much time for art at Imperial, she started drawing again when she came to Cambridge. “I needed an outlet,” she explains. “It first started when I was taking notes and I’d doodle images on the side of the paper. Then I started bringing in my sketches and during breaks I would work on them.” Fahmida found art was an effective way to take her mind away from her research and start to relax. “With drawing I could concentrate and refocus myself.”

Inspiration

Fahmida found a new focus for her drawings in 2018 when the Hindi-language film Padmaavat was released. She became entranced by the artistry of the period saga, and started creating complex pen and ink depictions of the film frame by frame, which she shares on her Instagram account using the name Fahmida Liza K.

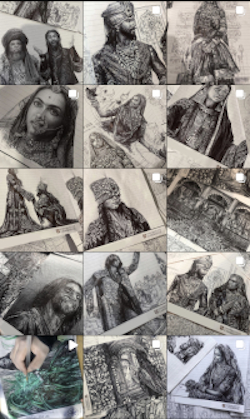

A montage of Fahmida's drawings from Padmaavat (below).

Padmaavat is based on an epic poem which follows the story of a Rajput queen. The film attracted controversy on its release because it depicts the Hindu practice of Jauhar, which is the self-immolation by women to avoid enslavement or rape by foreign invaders. Fahmida has watched the film over and over, and often has it playing in the background when she is working.

Padmaavat is based on an epic poem which follows the story of a Rajput queen. The film attracted controversy on its release because it depicts the Hindu practice of Jauhar, which is the self-immolation by women to avoid enslavement or rape by foreign invaders. Fahmida has watched the film over and over, and often has it playing in the background when she is working.

The film is directed by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Bhansali, who is known for his artistic vision. “Watching his films is more like watching art,” Fahmida says, “ he is like the Renaissance person of film. I started drawing from it because I appreciated the cinematography.” Fahmida’s painstaking and beautiful recreations attracted the attention of the Indian press, and were featured in a recent Times of India article celebrating the film’s third anniversary.

Padmaavat perhaps particularly strikes a chord with Fahmida, because although she was born and raised in Luton, her family is from Bengal. Her ancestry has led to another of her many interests, the Bishad Shindhu. Known in English as Ocean of Sorrow, this epic novel is regarded as a central work of Bengali literature, and is one of the first works produced during the Bengali Renaissance, which occurred in the 19th and early 20th century.

The book tells the metaphorical account of Muharram, in which Shia Muslims remember the death of the prophet Muhammad’s grandson in the Battle of Karbala. “If I were ever going to create my own original pictures, I would like to do ten drawings to illustrate the ten days of mourning,” she says.

Fahmida says anyone can pick up pencil or pen and start drawing. As proof of this, she was asked to give informal drawing classes to her fellow researchers at the start of lockdown. These went very well. “One of the points I make is art is not expensive – you don’t have to buy anything, you don’t have to be amazing, you can use a normal biro, which is what I do. If you make mistakes, you cover it up with the pen.”

Future plans

For the future, Fahmida plans to go into industry, at least to start. “Four years has been quite a long time in academia so I’d like to try something different for a bit and let’s see what I can do. When we were in high school we were told to write a letter to ourselves to say what we saw ourselves doing in ten years’ time. I said I want to be in Cambridge doing research, and that’s what I’m doing.” And by combining her science with her artistic passion, Fahmida has become her own Renaissance woman.