Published today in Science, the study shows how these molecular networks control key properties such as density and viscosity. The research is the result of a long-term collaboration led by Professor Michael K. Rosen (UT Southwestern) and Professor Rosana Collepardo-Guevara (Cambridge), as part of the Chromatin Collaborative Consortium, which meets annually at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, USA.

Cells contain millions of molecules that must be carefully organised for life to function. One of the most striking discoveries in nearly two decades is that cells gather many of these molecules into droplets that form without membranes, in a process similar to how oil separates from water. These condensates help regulate essential processes such as gene expression, DNA repair, and stress responses.

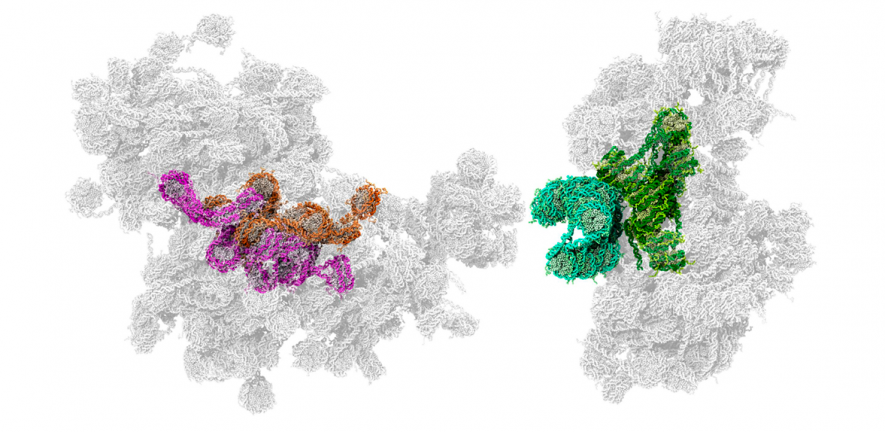

Until now, scientists had been unable to see what these condensates look like at the molecular scale. Chromatin condensates — droplets formed by chromatin, the DNA–protein complex that packages and organises our genes — are thought to help cells compartmentalise the genome, separating active and inactive gene regions and controlling when genes are switched on and off.

The experimental breakthrough was achieved by Dr Huabin Zhou in the Rosen Lab, who developed a cutting-edge cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) method capable of visualising individual molecules inside condensates for the first time. This was combined with a high-performance multiscale simulation framework developed by Dr Kieran Russell, Dr Jan Huertas, Dr Julia Maristany, and Dr Jorge R Espinosa from the Collepardo Group. Together, these approaches provided near-atomistic detail on the chemical organisation and material properties of chromatin condensates.

The simulations were powered by a new chromatin model developed by Dr Russell, recently released as a preprint, capable of studying systems ten times larger than previously possible. The findings represent a major step forward in understanding how the internal structure of chromatin droplets relates to their function in cells.

Professor Collepardo-Guevara described the work as “one of the most exciting moments of my career. Seeing the molecular structure of condensates for the first time transforms how we think about their role in cells, and gives us a roadmap for understanding how cells use physics to shape biology.”

Read the full article here

Watch here a short video showcasing the team’s new visualisations