A new mechanism of chemical control

In a recent publication, published in Nature Chemistry, titled Biomolecular condensates sustain pH gradients at equilibrium through charge neutralisation, Dr Hannes Ausserwöger, together with Professor Tuomas Knowles and colleagues, reveal that cells can generate small, local shifts in acidity, or pH, within droplets composed of proteins and nucleic acids. pH plays a crucial role in determining the behaviour of biological molecules; a familiar example is the stomach, which maintains a highly acidic environment to digest food and protect against microbes. This work was the result of a major collaborative effort involving contributors from across Europe, spanning both academia and industry. In particular, it involved close collaboration with colleagues in Dresden, Germany, from the Max Planck Institute of Cell Biology and Genetics and TU Dresden, as well as partners from Novo Nordisk in Denmark.

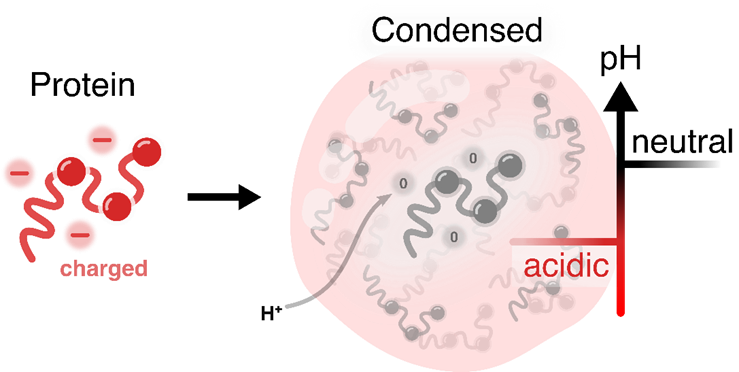

The study shows that cells can produce similar changes on a microscopic scale, creating small chemical zones that are either more acidic or more alkaline than the surrounding cytoplasm. In some droplets, multiple distinct pH regions can even coexist, demonstrating that condensates are not uniform blobs but finely tuneable chemical microenvironments. To investigate this, the researchers measured pH inside individual droplets using microdroplet experiments and complemented these findings with computer modelling of human proteins. Their results suggest that such pH gradients may be widespread in cells and could influence numerous chemical processes that were previously hidden.

Why this discovery matters

pH is one of the most basic chemical properties, influencing how molecules fold, interact, and react. By creating local pH differences, condensates give cells a simple, energy-free way to control chemical reactions in tiny spaces. This idea could inspire chemists to design new systems where molecules naturally create controlled environments for reactions. This discovery helps explain why cells use condensates for so many functions, from controlling genes to managing metabolism. It could also help us understand diseases, such as neurodegenerative conditions linked to condensates. In biotechnology and synthetic chemistry, creating tuneable pH zones could lead to new materials, reaction vessels, or tiny chemical systems.

A wider perspective

Condensates are not just passive clusters of molecules. They are tiny chemical worlds that shape how proteins and other molecules behave. By forming small, tuneable pH zones, cells have a simple, energy-efficient way to organise complex chemistry, revealing a hidden layer of control in life’s molecular machinery.

Looking ahead

Researchers are now asking how cells use these local pH shifts, how common they are across different organisms, and whether synthetic systems could mimic condensates to create custom chemical environments. Commenting on the broader significance of the findings, Dr Ausserwöger says, “It’s exciting to realise that protein systems, and nature more broadly, can exert functions in ways we didn’t know of before. The fact that such simple physical principles can create complex chemical control within cells opens up new ways of thinking about biological organisation.”

Moreover, since many aberrant protein aggregation processes that are associated with neurodegenerative diseases are likely to start inside condensates, the question arises of how disruptions in condensate formation, dynamics, or internal chemistry, such as altered pH regulation, might contribute to disease onset and progression. Understanding these links could not only illuminate fundamental cell biology but also inspire strategies to modulate or engineer condensates therapeutically, either to prevent pathological aggregation or to harness controlled phase separation for biomedical applications.